Text by Ingrid Luquet-Gad published in Heterotopia, exhibition catalogue, Pandore 2017

Heterotopia

Is a space still a space if it is porous, reversible, atomized, or even temporary? To put it otherwise, what type of space could we assign to the skin, to a membrane, or to an interface? The first answer that would spontaneously come to a philosopher’s mind would be: none. Classical thought, which values depth over surface and essence over appearances, has always sought to pierce the outer layer of things. And yet, this outer layer does more than merely separate two environments: “it preserves the very balance and the exchanges between them; it acts as a hub where influences and reactions mix” (1). This first step towards a reevaluation of the concept of the surface can be attributed to the French philosopher of science François Dagognet. In the early 1980s, Dagognet, who was also a doctor, a chemist, a geographer, a graphologist and a seismographer, published Faces, Surfaces, Interfaces, an ambitious endeavor to reexamine peripheries. A “dermatologist of things”, as he liked to call himself, Dagognet set in motion nothing less than an epistemological revolution. We must stop lamenting the invisibility of a supposedly hidden meaning, as he used to say. Against idealists who see souls just about anywhere, it is imperative that all efforts to gain knowledge be directed towards a materiological investigation of living beings. For everything is accessible to those who know how to open their eyes: “I merely have to recognize the invisible, although we miss quite often what is near and what is available” (2). The surface would therefore be the only depth that we could study – and thus acknowledge.

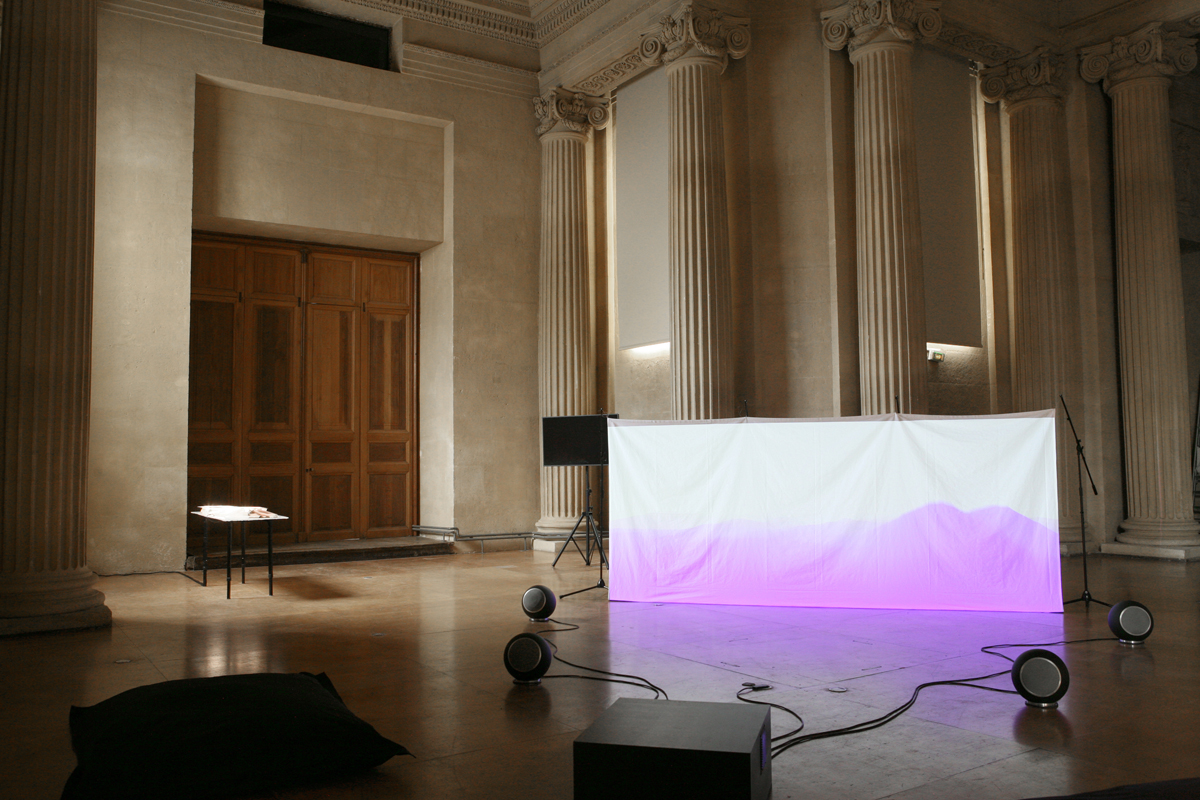

Over 40 years later, the scope of Dagognet’s research has become more radical. Where it once concerned only living things, it now applies to any kind of reality. A striking example of this is the meaning of the word “interface”, which condenses these very mutations, as it has gone from being used to abstractly describe a separation between two environments, to its current meaning, which characterizes a reality per se. Thus, a technological interface, the most accepted meaning of the word today, now refers to human-machine exchanges. Once a simple separation, it has become an apparatus. Thierry Fournier’s solo exhibition Heterotopia acknowledges this recent transformation of the surface and the essence, and explores its different visual consequences and its emotional ramifications through a constellation of seven works. In the chapel of the Saint-Denis Art and History Museum, the artist has set-up these fictions whose human scale contrasts with the monumentality of the space. Created in 2015 already, Ecotone, around which the project hinges, is a networked installation where the boundaries between past, present and future, conscious will and mechanical activation, are liquefied. In a video projection, a radioactive-pink rendered landscape ebbs and flows along with the inflections of hazy synthesized voices. Slightly slowed, these voices from beyond the grave read live tweets in which users express their desires: “I’d like so much” or “I’m dying to” fuel the algorithm.

Ecotone, network installation, 2015, exhibition view

The users’ emotional investment in the network – made up of singularities that may be isolated, but are nonetheless part of an entity that transcends them – is addressed again in I quit. Facing their web cams, individuals who have made the decision to give up social media discuss their choice one last time – through the very social networks they are leaving. Pulled this time towards its unconscious side, the same emotional burden also appears in Oracles. Using Apple messaging’s auto-suggest function, a series of texts were semi-automatically generated and printed on plexiglas plates. The user’s idiosyncrasies are blended with suggestions culled from the most common wording choices, thereby illustrating the entire palette of the 2.0 standardized emotions. In order to pursue François Dagognet’s materiological investigation, one would have to treat this particular type of living entity as an augmented living entity, and connected interfaces as singular, full-fledged places. Like a membrane, the interface ensures the exchanges between the two environments it separates – in this case, the world of humans and that of so-called artificial intelligence – can occur. At the edge and the combination of these environments appears a new register of desires: the human being and its mechanical extension begin to share the same pulse, the same dreams, the same words.

I quit, installation, 2017, exhibition view

Oracles, installation, 2015, exhibition view

By saying that these interfaces are places, the Greek etymology of “topos” comes to mind. From the outset, they are re-integrated into the long genealogy of counter-spaces, utopias, dystopias or heterotopias so dear to the type of modernity that wants to move away from an excessively burdensome reality. Heterotopia, as a concrete materialization of utopia, immediately recalls Michel Foucault’s writings. More so than the “Other Spaces” he developed theoretically during a conference in 1967, it is the analysis of another type of space that must interest us here, such as hospitals and clinics. As they integrate surveillance and data-collection technologies into their primary functions, these epistemological and economic machines are already preparing to produce a future humanity that will be shaped according to specific criteria, taken as standards. Foucault was among the first to consider the possibility of an infiltration of political and economic power into individuals’ very flesh, and to develop a theory about what is known today, put plainly, as biopolitics. But when it comes to reflecting upon the overlap between architecture and social entities, philosopher and activist Paul B. Preciado goes one step further. Published in 2010, Pornotopia reveals how gender was manufactured and how masculinity was redefined in post-war America through the lens of a very particular construction: the Playboy Mansion, built in 1959, and later reproduced across the country with the Playboy Clubs of the 1960s. Born in the wake of the invention of the birth-control pill and of the market roll-out of medical derivatives of the types of amphetamines that were used during the Vietnam War, Playboy magazine and the architectural ideal it conveyed brought about a redefinition of sexuality. From the single-parent family living in a suburban house, the model of heterosexual masculinity shifted towards the trope of the bachelor in his urban garçonnière. For Preciado, Hugh Hefner highlights the transition from a biopolitical disciplinary – Foucauldian – regime to neoliberal pharmacopornographical economies, in which communications and electronic surveillance systems, along with the regulation of sexual hormones, are the norm.

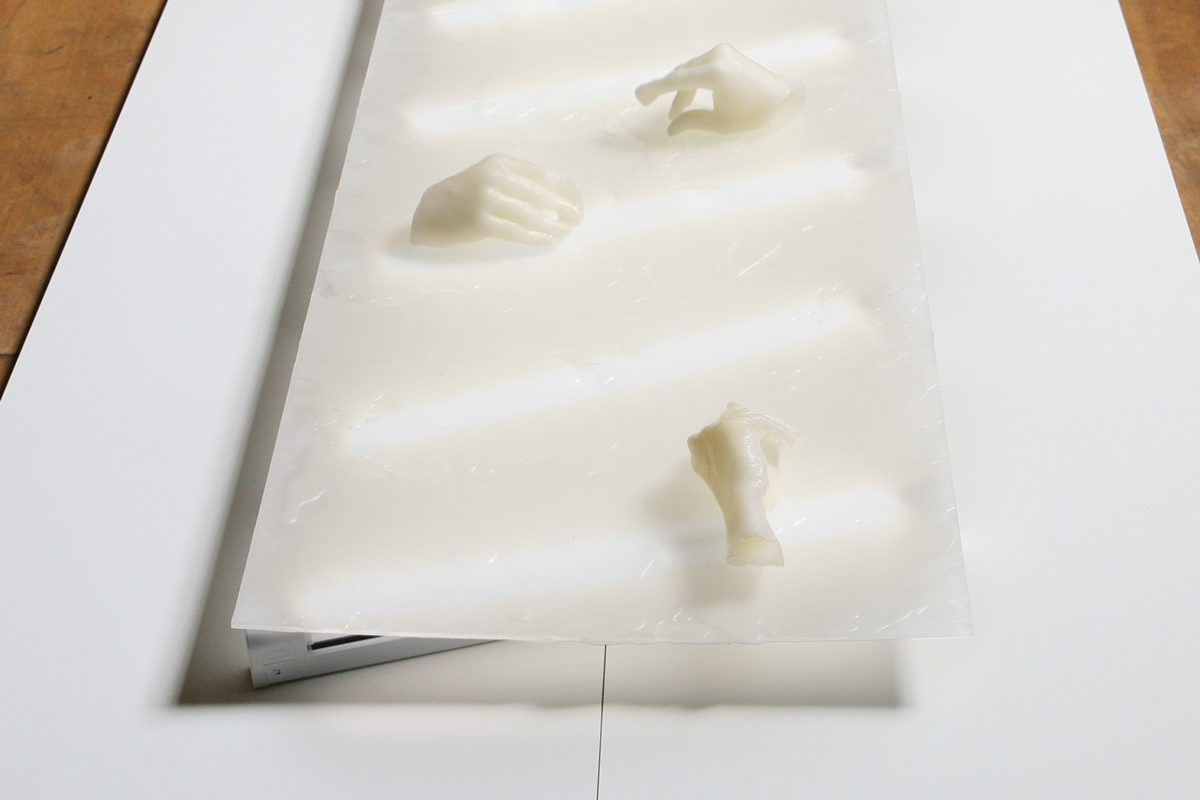

The invasion of such techniques into the domestic sphere continues today with their epidermic infiltration. Manipulated by users, the interface provides them with information and directly contributes to the production of their subjectivity. There is no longer any need for architecture or chemistry: when we are in its presence, the digital membrane brings us blissful serenity or wrenching loss when it is missing. At first, we figured we were using this new tool as any other – having clearly heard Hannah Arendt’s lesson, which taught us that the tool was merely an extension of the hand. We then realized that we were its addicted subjects, rather than its masters and owners: a specific set of gestures had been added to our body language, as demonstrated by Futur Instant, with its casts of hand gestures frozen during swipes or scrolls, which become completely absurd when removed from their context. What happens next is nothing more than the outcome of the prophecy foreseen with the Playboy mansion. Regarding the Mansion’s technological setup – which involved telephones, alarms, surveillance and loud-speaker systems – Beatriz Preciado stated early on: “In the Playboy Manson, we are closer to the technological assisted organism of John McHale, Buckminster Fuller, or Marshall McLuhan: The screen-eyes of the house are no longer organs but media prostheses” (3). The display of skins in flesh tones seen in the installation Nude – where the synthetic and the organic appear to have taken part in some unnatural alliances – seems to support the author’s observation. We move from the biopolitical – which is dissolved in the body – to a re-localization towards the surface of the skin, the contact zone that leads to both addiction and pleasure when we connect with the matrix-machine. The “body without organs” of the modernity has become a set of organs without a body. Or rather, it has become a single, last organ that is the sum of them all: the interface.

Ingrid Luquet-Gad, June 2017

(1) François Dagognet, Faces, Surfaces, Interfaces, Paris: 2007 (1982), Vrin. Foreword to the second edition, p. 7.

(2) Ibid., p. 10.

(3) Beatriz Preciado, Pornotopia. An Essay on Playboy’s Architecture and Biopolitics, New York: 2014 (2010), Zone Books, p. 116.

Nude, installation, 2017, exhibition view

Futur instant, installation, 2017, exhibition view